The Suicide CPR Initiative at USU Builds Interventions to Reduce Military Suicide Risk

The Suicide Care, Prevention, and Research Initiative (CPR) at the Uniformed Services University builds, scientifically tests, and implements suicide prevention programs by incorporating knowledge gained from Service members who have died by suicide as well as those with suicidal thoughts and/or behaviors.

|

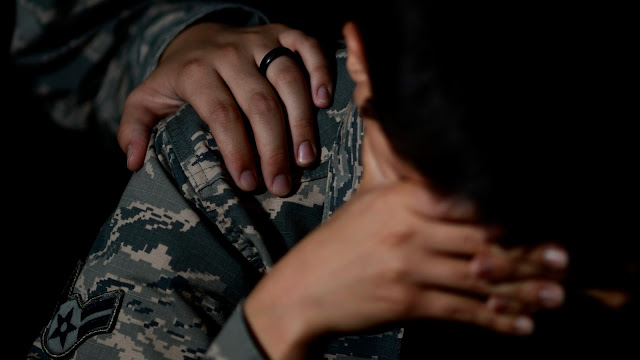

| The Suicide CPR Initiative provides support for chaplains, spouses, military leadership and other gatekeepers of service members. (U.S. Army photo by Michele Wiencek) |

September 25, 2023 by Hadiyah Brendel

September is Suicide Prevention Month. While numerous programs work to develop strategies to lessen the national suicide rate, a standout in the military community is the Suicide Care, Prevention, and Research (CPR) Initiative at the Uniformed Services University (USU).

The Suicide CPR Initiative builds, scientifically tests, and implements suicide prevention programs by incorporating knowledge gained from Service members who have died by suicide as well as those with suicidal thoughts and/or behaviors.

Drs. Marjan Holloway and Jessica LaCroix are director and deputy director, respectively, of the Suicide CPR Initiative. Housed where it began, the Initiative operates within the Department of Medical and Clinical Psychology (MPS) in the F. Edward Hébert School of Medicine at USU. Currently, more than 25 staff and faculty support the initiative’s work, and mentored within the program are eight MPS doctoral students.

Holloway is a clinical psychologist and intervention scientist. She serves as a professor in the MPS department, with a secondary appointment in USU’s Department of Psychiatry. Holloway joined the faculty in 2006 after having completed her postdoctoral training at the University of Pennsylvania. LaCroix, a social psychologist, is a research assistant professor in the MPS department. She joined USU as a contract employee of the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, in 2016.

The Suicide CPR Initiative, formerly the Laboratory for the Treatment of Suicide-Related Ideation and Behavior, formed in 2006. The new name better exemplifies the initiative’s goal within the Department of Defense (DoD) to provide suicide prevention care to the military community.

|

Dr. Marjan Holloway (left) is Director of the Suicide CPR Initiative in the MPS department at USU. Dr. Jessica LaCroix (right) is Deputy Director of the initiative. (Photo credit: Tom Balfour, USU) |

Building Interventions

What separates the Suicide CPR Initiative from other suicide prevention research programs is its focus on designing innovative primary (directed to all service members), secondary (directed to service members with suicidal thoughts and behaviors), and tertiary (directed to service members following a suicide-related event) interventions to care for the military community.

Collaboration with the military community and aligning with the priorities set forth by the White House and the DoD drives all of the program’s endeavors.

LaCroix calls it “community-based participatory research,” meaning, they engage with the community they work to serve. The researchers gather lessons learned from individuals who have died by suicide as well as those who have experienced suicidal thoughts and/or behaviors.

They incorporate stories from discussions with family and military community members affected by those who have died by suicide and those who have survived a suicide attempt. The Suicide CPR team also collaborate with chaplains and military leadership who routinely engage with and serve as gatekeepers for service members. This data builds the interventions.

“We’re working with partners across the military community to develop programs that meet the DoD’s strategic goals for suicide prevention,” LaCroix added.

The Mil-iTransition program is one example of this collaboration in motion. The Mil-iTransition program is a peer-based program, developed in recent years by the Initiative. This program is for active duty Service members who have received an “unfit for duty” notice from the Medical and Physical Evaluation Boards (MEB/PEB).

Medical separation may cause higher than usual transition-related stress due to limitations in physical, emotional, and social functioning. Additionally, an “unfit for duty” notice may impact the service member’s sense of worth and identity.

Mil-iTransition is a telephone-based, low-intensity intervention designed for delivery by veteran peers who have experienced the MEB/PEB process. The program’s goals are for peer facilitators to make a connection with the transitioning Service member. The connection enhances their coping strategies, targets problematic thoughts, and maximizes overall safety.

The Suicide CPR Initiative worked directly with medically-separated veterans to build this program. Hired as peer supporters, veterans worked with the research team on creating the content of the intervention, the delivery of the intervention, and the evaluation of the intervention. Sixty Service members and veterans medically separated from the service were also interviewed to learn more about their experiences.

“Those stories went into building the Mil-iTransition program,” LaCroix says.

Another example of an intervention involves the Rational-Thinking, Emotion Regulation, and Problem-Solving, or REPS curriculum. REPS is a mental fitness program geared toward early enlisted Service members. Almost near completion, the REPS-online will soon be available to the military community on MilLife Learning. The smartphone application for REPS will target thoughts, emotions, and behaviors for early-career Service members to provide appropriate strategies and resources. The REPS-online program has three more years of development and empirical testing.

Development, refinement, and pilot testing of the REPS program occurred at the Training Support Center Great Lakes in North Chicago, IL. Originally funded by the Defense Suicide Prevention Office (DSPO), REPS is another example of how the Initiative works with the military community to remain culturally relevant.

DoD partnerships provide other data in support of the Suicide CPR Initiative’s mission. For example, the Departments of the Air Force and Navy have partnered with the initiative to standardize their suicide death review processes. Tasked by the DSPO, the initiative is to create the DoD Standardized Suicide Fatality Analysis (DoD StandS) framework. Lessons learned and actionable recommendations put forth to military leadership will inform the development of new interventions to reduce suicide risk within these communities.

Testing Interventions

In light of such an urgent and continuous need, how are the interventions scientifically tested? Where appropriate, the programs go through randomized controlled trials. In these research trials, depending on design, participants are randomly assigned to receive an intervention or not in order to establish the intervention’s efficacy or effectiveness.

While the gold standard for research, Holloway stressed that this process is not feasible in every instance. The entire process can take years to complete, from initiating the research to replicating findings, to eventually putting the program into effect, and convincing stakeholders to maintain the program.

One way to test the interventions robustly and yet swiftly is by looking at the acceptability of the program. Holloway says you can “design the best program that's incredibly effective within a research setting, but if a Service member does not see the value-added and does not accept it as helpful, then there’s no point.” So they examine how individuals within the military-community engage with the different programs offered.

Program evaluations are another strategy used. In this method, evaluation parameters establish to what extent people utilize the strategies taught to them and how the program can improve over time. The goal is to best understand the reasons behind a program’s success. Another goal of this evaluation is to discover ways to make a program more effective and more helpful for the target audience.

Implementing Interventions

The interventions reach the military community primarily in three ways. First, through collaborations and coordination with funding organizations such as the DSPO and the Military Operational Medicine Research Program. Second, through scientific presentations, technical reports, and peer-reviewed publications, and third, through educational programs.

For example, two programs created by the Suicide CPR Initiative are currently available on MilLife Learning, a service offered through Military OneSource. The courses are Chaplains-CARE Training Program and Special Operations Cognitive Agility Training (SOCAT).

The Chaplains-CARE Training Program teaches specific techniques that foster direct, open, and honest conversations with a Service member who is having suicidal thoughts or behaviors. Collaborations with the Navy Office of the Chief of Chaplains and the Navy Chaplaincy Research Community of Interest built the program. Feedback provided by learners was overwhelmingly positive, especially for the in-person program, and there is preliminary evidence that Chaplains-CARE may improve overall feelings of preparedness, reduce reluctance, increase self-efficacy, contribute to greater likelihood to intervene with suicidal Service members, and improve competency in delivery of suicide intervention strategies.

SOCAT, or Special Operations Cognitive Agility Training, is a training program designed for spouses and partners of special operators. The course works to build resiliency, or cognitive agility, of spouses to bolster their mental health. Both courses are free to enroll.

Providing Care, Prevention, and Research

“Suicide is still such a stigmatized issue in our society, and in the context of the military as well. We have to continue to be very protective of our Service members, and the family members, of those who think about suicide or who attempt suicide,” Holloway says.

Yet, it remains vital to share their stories. “We want to make sure [Service members] have opportunities to have their voices heard. The best way to do this, which is what other researchers do, too, is to give individuals the element of choice,” Holloway says.

When asked what Service members and their families can do to spread awareness about suicide prevention throughout the year, Holloway says to “appreciate that mental fitness is AS IMPORTANT and valuable as physical fitness.”