“Out of Need Comes Innovation”: MHS Conference Continues with Discussions of the Future

The 2024 Military Health System Conference in Portland, Oregon continues with further discussion of the new MHS strategic plan.

April 11, 2024 by Zachary Willis, and Hadiyah Brendel

Panelists and speakers from USU continued discussion at the Military Health System Conference in Portland, Oregon, on day two, with topics ranging from exciting new research to the strength of the Uniformed Services University’s (USU) Postgraduate Dental School, our country’s preparedness for a national disaster, and even the role of games in medical education.

Research and Innovation in the MHS

Dr. Mark Kortepeter, USU’s Vice President for Research, and Assistant Vice President for Research Initiatives and Compliance Dr. Laura Brosch, used their breakout session to highlight the vast amount of innovative and cutting edge research being conducted by the University’s centers.

Referencing work such as bioprinting at USU’s Center for Biotechnology, or 4DBio3, examinations of heat illness by the Consortium for Health and Military Performance (CHAMP), the Armed Forces Radiobiology Research Institute’s (AFRRI’s) studies into radiation injury assessment, and the Murtha Center Center Research Program’s development of a machine learning algorithm, Kortepeter noted that linking USU’s centers together in “innovation hubs” was one of the ways in which the University was embracing recent trends in research innovation.

“We established these four hubs – combat casualty care, infectious disease, brain health, and education simulation – with the idea that, by bringing these folks together, there’s a way for them to work across their individual specialties,” said Kortepeter.

Brosch spoke for the latter half of the session, delivering a spirited call for partnership between USU and military treatment facility clinical researchers. Through research training and education, collaboration, faculty appointments, funding for research projects, and access to a wider audience, the benefits of working with the University were all too clear.

“Look at [USU] as your academic home,” said Brosch. “We have a huge national faculty; we are already in your midst. If you’re interested in research or you have staff who are interested in research or they have a great idea and really want to talk to somebody about it, they can contact us.”

Brosch outlined the University’s research capabilities, referencing a USU team made up of not only faculty members, but alumni and students as well, who were able to invent a life-saving PPE device during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Out of need comes innovation,” said Brosch. “Dr. Martinez-Lopez identified us as a system, and we’re an organ in that system. This organ trains, teaches, and force-generates, but we also fill a critical research gap.”

Graduate Dental Education: Building a Bite for the Fight

“It’s not just about teeth in military dentistry,” said Dr. Drew Fallis, Executive Dean of USU’s Postgraduate Dental College (PDC).

The session, “Building a Bite for the Fight,” was a comprehensive look into the PDC through its relevance to total force readiness, the challenges faced on a national level, and the ways in which the PDC should be used as the leading example of how intentional and well thought out collaborations across military medicine can greatly elevate the quality of education, care, and research throughout the MHS.

“One of the first things that was accomplished after the establishment of the Postgraduate Dental College was to identify needs and gap areas for the Department of Defense,” said Fallis. “And in the last two years, 100% of the Master’s projects that were used for the PDC aligned with one of the needs of the Department of Defense.”

The presentation noted that 38% of graduating dental students in the civilian sector planned to seek additional training after dental school, highlighting the challenges faced by dentistry as a whole; however, Fallis added that the education given to PDC students is designed to fill in those skill gaps and provide them with advanced skills that would not be found in general dental school.

Fallis also described the benefits of an MHS model for Graduate Dental Education through the establishment of an Integrated Advisory Board by the DHA to enhance processes and initiatives across the military departments (MILDEPS). He also discussed clarity of roles and responsibilities in support of Graduate Dental Education, codifying policies, and enhancement of the processes and procedures in support of mission readiness, including identification of the best personnel to support the mission as well as strong design of education and training programs to best develop that personnel whether student or faculty.

Additionally, Fallis emphasized that the success that can be found through collaboration across the MHS can rival or even surpass anything seen in the civilian sector, explaining that the collaboration between the MILDEPS and USU resulted in the establishment of the PDC, which now “provides the largest portfolio of Graduate Dental Education programs in the nation, and the professional developmental pathways to support them.”

In the follow-up question and answer period to Fallis’s session, Dr. Paul Cordts, Deputy Assistant Director for Medical Affairs for the MHS, praised the program, saying that the USU PDC was leading the MHS and the nation.

From the Battlefield to Your Local Hospital: Building an Integrated Framework for Wartime Casualties (Part 1 & Part 2)

In this two-part session, panelists detailed the interdependent components of patient movement within the MHS from point-of-injury, to point-of-evacuation, to definitive care, through to a successful discharge at home.

They discussed how patient movement will change in the face of a large-scale casualty event where care for Service members transfers to civilian hospitals. Stressing the importance of information moving seamlessly with patients during these transitions, the panel highlighted the necessity, and challenges, of this coordination.

Session 1 panelists included Dr. Jeffrey Freeman, director of USU’s National Center for Disaster Medicine and Public Health (NCDMPH), Navy Capt. (Dr.) Jeffrey Bitterman, INDOPACOM Surgeon, Air Force Brig. Gen. (sel) Eveline F. Yao, U.S. Transportation Command Surgeon, and Air Force Col. (Dr.) M. James Higgins, U.S. Northern Command Surgeon.

Brig. Gen. (Dr.) John R. Andrus, Joint Staff Surgeon, joined the panel in Part 2 of the sessions. CDR Manuel Beltran served as moderator, and helped to lead an engaging question and answer session with the audience.

Freeman detailed how NCDMPH’s National Disaster Medical System (NDMS) Pilot Program integrates into a broader framework. That framework designs a response to command, control, and coordinate the care of combat casualties into civilian medical care.

In responding to how the MHS confronts the requirements of a large-scale combat operation and other catastrophic events on the homeland that will far exceed anything the nation can possibly sustain in a steady-state, Freeman says “there is simply no sustainable business model to prepare for this scale of an event.”

However, he adds, the answer lies in the three vectors of the program and “how we are reshaping the NDMS Pilot Program now. Which is to say we are going to be successful; we are going to prepare the nation for an event of that scale.”

Envisioning and Creating the Future of Military Medical Education

With the increasing prevalence of digital technology in the professional and educational environment, Dr. Eric Elster, dean of the Hebert School of Medicine at USU, discussed the impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI) on the military medical education at USU. Dr. Paul Cordts, Deputy Assistant Director of Medical Affairs for the MHS, served as moderator and provided key feedback during the Q&A following the discussion.

Those in the medical field are life-long learners, and Elster says “I think what you’re going to see with this AI revolution is it makes it more palpable.” He adds, “I believe medicine is a full contact sport. And I think AI will buy us more time. Give us more time for the power of that clinical environment as humans with one another and with our patients. We have to pay attention to the balance. But I see it as an accelerator.”

Even GPT-4’s release prompted Elster to question its utilization in the four domains of education, research, clinical care, and back-end functions. He emphasized USU President Woodson’s sentiment that you can’t be afraid of the calculator because the abacus was fine, but prepare to utilize new technology.

Elster spoke particularly about the Joint Expeditionary Medical Officer Project at USU. The project identifies the most operationally relevant knowledge, skills, and abilities covered in the School of Medicine’s Molecules to Military Medicine curriculum.

“It is a phenomenally exciting time to be in medicine. Medicine will change in the next 20 years more than it changed in the past 50 years,” says Elster.

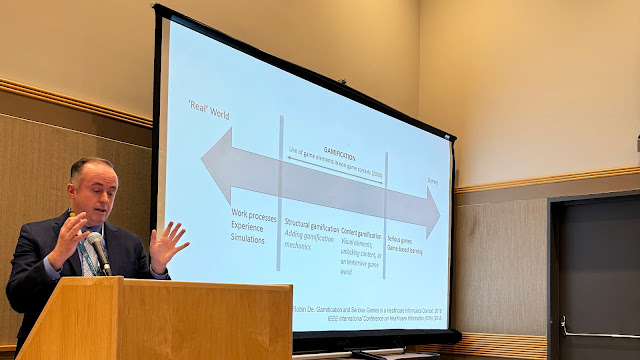

Gamification in Medical Education: Why & How?

In one of the final sessions of the day, Dr. William Kelly, professor of Medicine at USU, shifted the conversation to the theory and fun behind “gamifying” medical education, highlighting both the incredible results that gamification has produced, as well as some of the challenges and limitations that have appeared. Gamification uses elements of gaming to improve learning experiences.

“That emotional connection [provided by gamification] is just different,” explained Kelly. “There’s a novelty - it’s not the same small group, the same conference, the same team meeting that you’re doing every week, it’s something different that you can add.”

While gamification has a much longer history, Kelly noted that two-thirds of the published literature on the subject only came out within the past 11 years, with 215 papers submitted last year marking a growing desire for this alternative approach to learning.

|

Dr. William Kelly, professor of Medicine at USU, describes the theory and fun behind “gamifying” medical education. (Photo credit: Zachary Willis, USU) |

Kelly went on to give an example of success in gamification through a game developed to teach chest tube placement. In the game, the player gets the opportunity to practice correct placement in a digital scenario, allowing them more time to hone their skills before practicing in a physical space.

“The next day, you have them come into a lab, and you have them put in the chest tube,” explained Kelly, “and there’s some overlap but there’s some statistical significance that, if you did the game, your score is a little bit higher.”

He continued, remarking that many of the studies often are only able to provide short-term outcomes due to short testing windows and simple games; however, with greater advances in theory and technology, there is potential to add greater nuance and refinement to these studies, enabling further development of this forward-thinking approach to engagement in education.

Throughout the session, Kelly continually urged his audience to try out gamification for themselves, noting that even the simplest games can bring results in knowledge acquisition and retention.

“There’s a lot of talk about work/life balance,” said Kelly. “Why not bring some of the fun stuff from home into your education and your work?”